From the WashU School of Medicine Outlook Magazine…

Genomic medicine. Personalized medicine. Precision medicine.

When it comes to interpreting and applying big data in health care, people may not agree on the best terminology. Most agree on one thing: Big data is an abstract, intimidating concept.

DNA sequencing generates millions of data points for a single individual. Clinical trials yield massive amounts of treatment information. The electronic health record (EHR) expands with every patient encounter. And wearable fitness trackers and apps — which measure steps taken, food consumed, heart rate, blood pressure and sleep patterns, open up a whole new area of possibility.

Big data is coming at medical professionals from all directions. Many have no idea how to effectively leverage it for patient care.

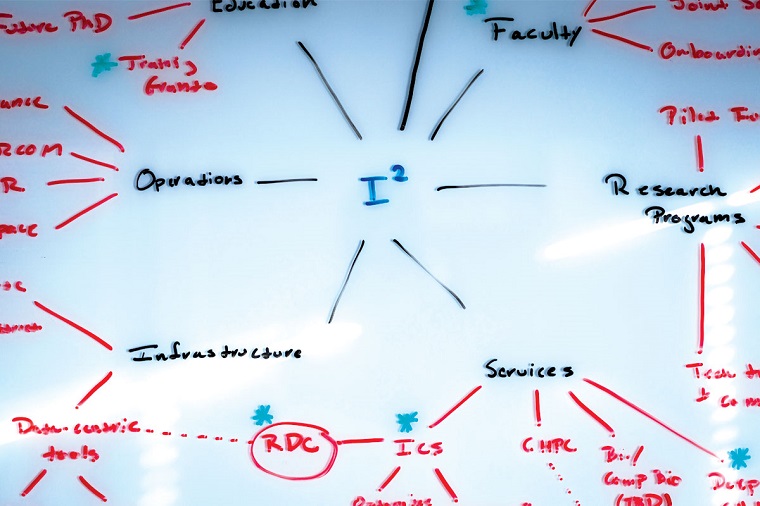

Philip R.O. Payne, PhD, is an internationally recognized leader in informatics, a field that translates big data into actionable knowledge. As inaugural director of the university’s Institute for Informatics, he leads the way he speaks — at double speed. In 20 months of existence, the institute has made significant inroads at this large, decentralized university.

For Payne, the path forward is clear.

“If you ask physicians what they want, it’s the equivalent of a ‘patients like mine’ button on their electronic device,” he said.

“They tell us, ‘Given the patient that’s in front of me right now, show me similar patients who have been seen in the past six months, one year or 10 years. What treatment decisions were made? Who had the best outcomes? Who didn’t?’

“Physicians want to know, based on their wisdom and the wisdom of colleagues, how to optimize outcomes for the patient in front of them.”

Information overload

Provider burnout nationally is at an all-time high, with doctors citing such factors as job complexity and having too few hours in the day. By some estimates, EHR upkeep requires 31 percent of physicians’ time.

A few decades ago, doctors could stay abreast of medical advances by reading scholarly journals. Now, it’s virtually impossible to keep up with the constant flow of information.

“Human short-term memory is optimized to remember seven pieces of information at a time, plus or minus two,” said Payne, also the Robert J. Terry Endowed Professor. “Informatics is essential to figuring out how we connect the dots between those millions of data points, contextualize them and deliver them back to clinicians who may have only 10 minutes with a patient to interpret and act on that information.”

Payne envisions a new landscape — where doctors and researchers have the necessary tools and expertise to extract meaningful information within vast data sets.

When many people hear the word informatics, Payne said, they associate it with interpreting the human genome, but that’s just one aspect of the institute’s work.

A top priority is improving EHR efficiency. The EHR requires a mental shift for some physicians who are used to free-form documentation of patient encounters on paper versus a more rigid, checkbox system that perhaps even influences medical thinking. Many clinicians find it clunky, burdensome and disruptive. Institute team members are shadowing clinicians at the point of care to design technologies that adapt to workflow.

Efficiently designed systems can close the gap between digesting the data and making clinical decisions, Payne said. “The real challenge is not getting more data. It’s figuring out what to do with what we already have.”

Recently, Payne and David H. Gutmann, MD, PhD, the Donald O. Schnuck Professor and director of the Neurofibromatosis (NF) Center at Washington University, employed informatics to predict symptom severity in children with NF1, a genetic disorder that causes brain and nerve tumors, as well as autism spectrum disorder (ASD). NF1 varies widely in severity and symptoms — from harmless brown spots on the skin and benign bumps to optic gliomas and malignant cancers. Parents don’t know which symptoms might manifest in their child.

In a matter of hours, using computer analytics and existing NF1 patient data, Gutmann and Payne improved risk models that others had created following months of painstaking deliberation in conference rooms. With even greater specificity, they outlined various NF1 subtypes, their trajectories and associations with optic gliomas and ASD.

This information allows families to plan ahead, and alerts clinicians as to whether additional imaging or other interventions are warranted.