Many children treated for childhood malnutrition in developing countries never fully recover. They suffer from stunted growth, immune system dysfunction and poor cognitive development that typically cause long-term health issues into adulthood.

Now, new research from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research involving malnourished children in Bangladesh has implicated specific types of gut bacteria in the small intestine as a cause of their stunted growth. Such bacteria contribute to disease in the lining of the small intestine — a condition called environmental enteric dysfunction — which impairs the absorption of nutrients from food and suppresses growth factors necessary for healthy development.

The research, published July 23 in The New England Journal of Medicine, may help scientists design new therapies for malnourished children who remain stunted and underweight even after receiving therapeutic foods.

In an editorial that accompanies the study, Ramnick J. Xavier, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, called the new research “reminiscent of the identification of Helicobacter pylori as a cause of ulcers.” According to Xavier, the work ties a disease to a group of bacteria that colonizes a specific region of the gut and illustrates the benefits of integrating global health with basic mechanistic studies of the causes of disease.

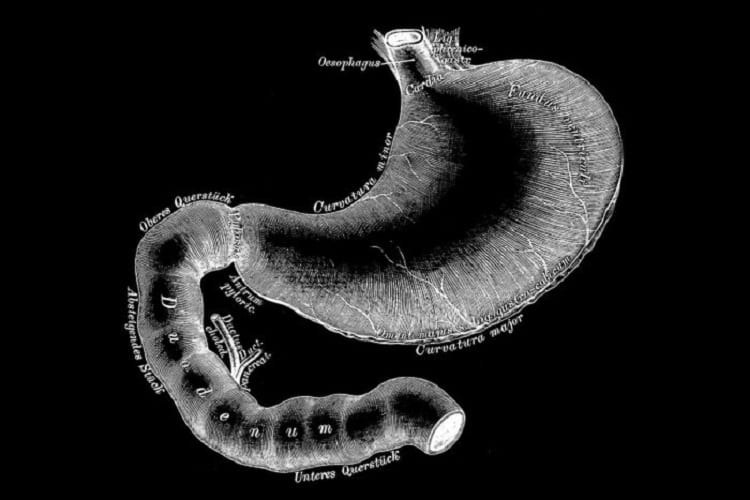

The gut microbiome has a symbiotic relationship with its human host. Evidence is emerging about its critical contributions during the early years of life to healthy growth and development. Much research involving the gut microbiome has focused on bacteria measured in fecal samples, which are not necessarily representative of the microbial communities living in different regions along the length of the gastrointestinal tract. The researchers were interested in the upper small intestine — the region of the gut immediately following the stomach — because it is largely unstudied and because there were hints that it could play an important role in malnutrition.

“Much of the body’s nutrient absorption takes place in the small intestine,” said senior author Jeffrey I. Gordon, MD, the Dr. Robert J. Glaser Distinguished University Professor and director of the Edison Family Center for Genome Sciences & Systems Biology at the School of Medicine. “The small intestine is lined with finger-like projections called villi, which increase the absorptive surface area of the gut. In environmental enteric dysfunction, these villi are damaged and collapse, causing inflammation in the wall of the gut and reducing its ability to absorb nutrients. This disorder has been very difficult to diagnose, and its cause is enigmatic as is its relationship to the many manifestations of malnutrition, including short stature (stunting). Our study was designed to address these questions. The results have helped us to decipher disease mechanisms and also provide a rationale for developing new therapies that target the small intestinal microbiome.”