Smell a cup of coffee.

Smell it inside or outside; summer or winter; in a coffee shop with a scone; in a pizza parlor with pepperoni — even at a pizza parlor with a scone! — coffee smells like coffee.

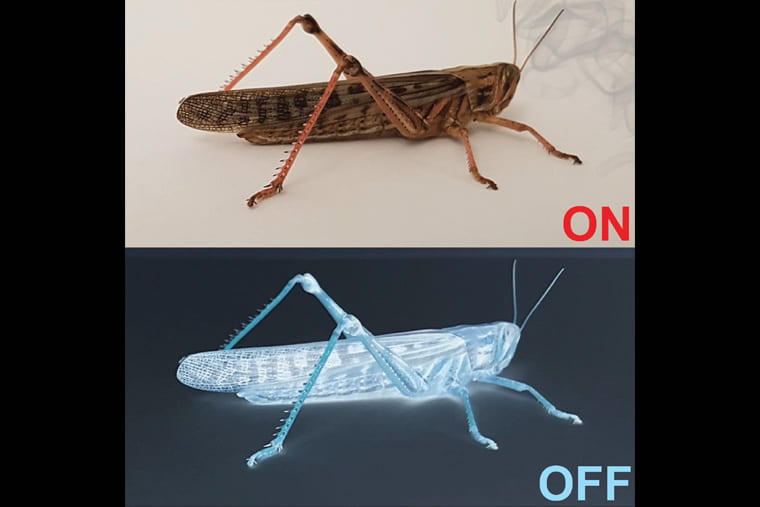

Why don’t other smells or different environmental factors “get in the way,” so to speak, of the experience of smelling individual odors? Researchers at the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis turned to their trusted research subject, the locust, to find out.

Raman

What they found was “surprisingly simple,” according to Barani Raman, PhD, professor of biomedical engineering. Their results were published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

Raman and colleagues have been working with locusts for years, watching their brains and their behaviors related to smell in an attempt to engineer bomb-sniffing locusts. Along the way, they’ve made substantial gains when it comes to understanding the mechanisms at play when it comes to locusts’ sense of smell.

To understand how it is that a locust can consistently recognize smells regardless of context, they took a cue from Ivan Pavlov. Like Pavlov’s dogs, locusts were trained to associate an odor with food, their preference being a blade of grass. After going a day without food, a locust was exposed to a puff of odor (a puff of hexanol or isoamyl acetate), then given a blade of grass. In as few as six such presentations, the locust learned to open its palps (sensory appendages close to the mouth) in expectation of a snack after simply smelling the “training odorant.” Just like us recognizing coffee, the trained locust could recognize the odor and did not let other factors get in the way.

At this point, researchers began looking at which neurons were firing when the locust was exposed to the odor under different conditions, including in conjunction with other smells, in humid or dry conditions, when they were starved or fully fed, trained or untrained, and for different amounts of time.