Marie Kondo herself couldn’t do it any better.

Usually cells are good at recognizing what doesn’t spark joy. They’re constantly cleaning house — picking through their own stuff to clear out what no longer works.

Damaged or superfluous organelles. Proteins that don’t fold just so.

But what happens when the cell fails to recognize trash? Accumulation of defective cellular material has been implicated in disorders such as Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s disease and Lou Gehrig’s Disease/ALS, where this trash blocks neurons from transmitting signals.

Now, researchers at Washington University in St. Louis have uncovered a previously unknown structural feature of living cells that is critical to tidying up.

The research, led by Richard S. Marshall, research scientist, and Richard Vierstra, the George and Charmaine Mallinckrodt Professor of Biology in Arts & Sciences, is published in the April 4 issue of the journal Cell.

New receptors for taking out the trash

One major way that cells clean up their trash is through autophagy. In this process, cells engulf unwanted material in vesicles that are then deposited in a trash bin called the vacuole or lysosome. There, the trash is degraded and its building blocks reused.

Key to this recycling process are the receptors that recognize the trash and tether it to a protein called ATG8 that lines the engulfing vesicle. Previously, all of these receptors were thought to be related and bound to ATG8 via the same mechanism.

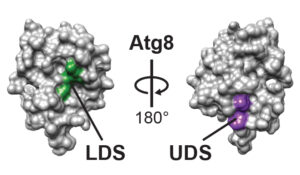

“There is the binding site on ATG8 that everyone knew about before, and how it interacts with autophagy receptors,” Marshall said. “But we found that if you completely rotate the molecule 180 degrees, there is the new site on the opposite side that recognizes a long list of additional cargo receptors.

“A whole slew of proteins in plants, yeast and humans are using this new binding site and its suite of cognate receptors to interact with ATG8,” he added.