Examining brain folds — as unique to an individual as fingerprints — could hold key to new diagnostic tools

From the WashU Newsroom…

During the third trimester, a baby’s brain undergoes rapid development in utero. The cerebral cortex dramatically expands its surface area and begins to fold. Previous work suggests that this quick and very vital growth is an individualized process, with details varying infant to infant.

Research from a collaborative team at Washington University in St. Louis tested a new, 3-D method that could lead to new diagnostic tools that will precisely measure the third-trimester growth and folding patterns of a baby’s brain.

The findings, published online March 5 in PNAS, could help to sound an early alarm on developmental disorders in premature infants that could affect them later in life.

“One of the things that’s really interesting about people’s brains is that they are so different, yet so similar,” said Philip Bayly, the Lilyan & E. Lisle Hughes Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the School of Engineering & Applied Science. “We all have the same components, but our brain folds are like fingerprints: Everyone has a different pattern. Understanding the mechanical process of folding — when it occurs — might be a way to detect problems for brain development down the road.”

Working with collaborators at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, engineering doctoral student Kara Garcia accessed magnetic resonance 3-D brain images from 30 pre-term infants scanned by Christopher Smyser, MD, associate professor of neurology, and his pediatric neuroimaging team. The babies were scanned two to four times each during the period of rapid brain expansion, which typically happens at 28 to 30 weeks.

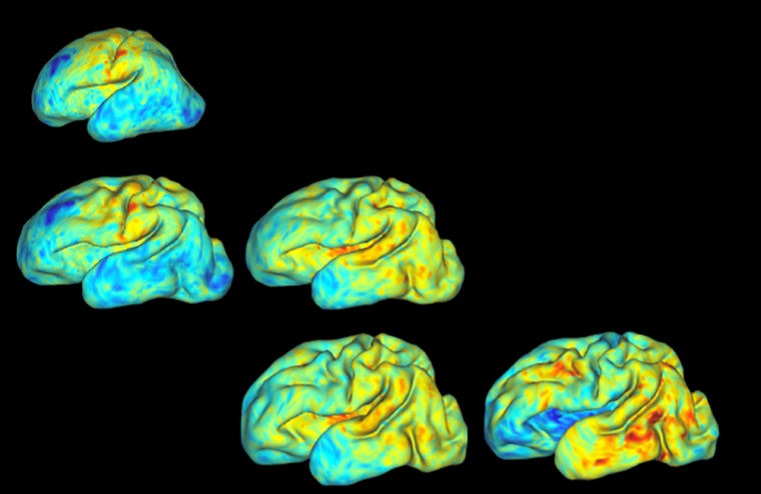

Using a new computer algorithm, Bayly, Garcia and their colleagues — including faculty at Imperial College and King’s College in London — obtained accurate point-to-point correspondence between younger and older cortical reconstructions of the same infant. From each pair of surfaces, the team calculated precise maps of cortical expansion. Then, using a minimum energy approach to compare brain surfaces at different times, researchers picked up on subtle differences in the babies’ brain folding patterns.