A new imaging technique developed by engineers at Washington University in St. Louis can give scientists a much closer look at fibril assemblies — stacks of peptides that include amyloid beta, most notably associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

These cross-β fibril assemblies are also useful building blocks within designer biomaterials for medical applications, but their resemblance to their amyloid beta cousins, whose tangles are a symptom of neurodegenerative disease, is concerning. Researchers want to learn how different sequences of these peptides are linked to their varying toxicity and function, for both naturally occurring peptides and their synthetically engineered cousins.

Now, scientists can get a close enough look at fibril assemblies to see there are notable differences in how synthetic peptides stack compared with amyloid beta. These results stem from a fruitful collaboration between lead author Matthew Lew, PhD, associate professor in the Preston M. Green Department of Electrical & Systems Engineering, and Jai Rudra, PhD, associate professor of biomedical engineering, in WashU’s McKelvey School of Engineering.

“We engineer microscopes to enable better nanoscale measurements so that the science can move forward,” Lew said.

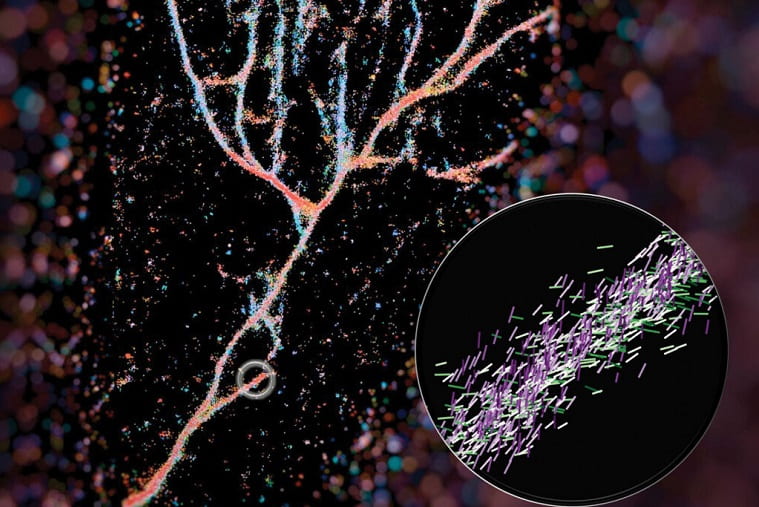

In a paper published recently in ACS Nano, Lew and colleagues outline how they used the Nile red chemical probe to light up cross-β fibrils. Their technique, called single-molecule orientation–localization microscopy (SMOLM), uses the flashes of light from Nile red to visualize the fiber structures formed by synthetic peptides and by amyloid beta.

The bottom line: these assemblies are much more complicated and heterogenous than anticipated. That’s good news because it means there’s more than one way to safely stack proteins. With better measurements and images of fibril assemblies, bioengineers can better understand the rules that dictate how protein grammar affects toxicity and biological function, leading to more effective and less toxic therapeutics.