Bayly

Naval warfighters may be exposed to explosions, impacts or high accelerations that increase their risk for traumatic brain injury. A team of researchers led by Philip Bayly, PhD, at Washington University in St. Louis plans a comprehensive study of skull-brain mechanics using imaging, computer and preclinical models to study the strains and stresses of the brain induced by skull motion in these types of interactions.

Bayly, the Lee Hunter Distinguished Professor and chair of the Department of Mechanical Engineering & Materials Science in the McKelvey School of Engineering, and collaborators at the University of Delaware and Dartmouth College will conduct the research with a three-year, $700,000 grant from the Office of Naval Research. The work is expected to shed light on the ways that the magnitude, location and orientation of mechanical loading of the brain can influence the characteristics of a traumatic brain injury. Such injuries affect about 1.4 million people in the U.S. annually, both military personnel and civilians of all ages.

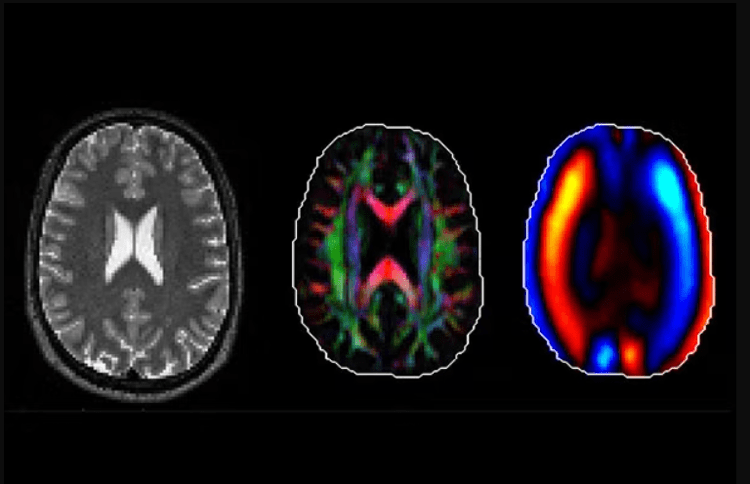

Bayly and his team will use several forms of imaging at the Neuroimaging Lab Research Center and the Small Animal Magnetic Resonance Facility in the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology at Washington University School of Medicine to study the behavior of the brain and skull in a preclinical model and to take measurements of the interactions between a helmet, the skull and the brain in healthy volunteers. Results of the imaging also will allow them to study the direction-dependent mechanical properties of brain tissue.

“We are looking at how shear waves move in the brain,” Bayly said. “A blast from an explosion creates a big pressure wave in air, which is transmitted into the skull potentially creating large, damaging, shear waves in the brain. In our experiments, we will generate small, non-injurious shear waves to probe how the brain might respond to blasts and other sources of skull motion.”

To understand shear waves, Bayly suggests visualizing gelatin (Jell-O) as a model for the brain. It is hard to change the volume of a block of gelatin but easy to deform it into a different shape. Shear waves are waves that deform the gelatin (or brain tissue), making them potentially more damaging, Bayly said.