A realtor sends a prospective homebuyer a blurry photograph of a house taken from across the street. The homebuyer can compare it to the real thing — look at the picture, then look at the real house — and see that the bay window is actually two windows close together, the flowers out front are plastic and what looked like a door is actually a hole in the wall.

What if you aren’t looking at a picture of a house, but something very small — like a protein? There is no way to see it without a specialized device so there’s nothing to judge the image against, no “ground truth,” as it’s called. There isn’t much to do but trust that the imaging equipment and the computer model used to create images are accurate.

Lew

Now, however, research from the lab of Matthew Lew, PhD at the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis has developed a computational method to determine how much confidence a scientist should have that their measurements, at any given point, are accurate, given the model used to produce them.

The research was published Dec. 11 in Nature Communications.

“Fundamentally, this is a forensic tool to tell you if something is right or not,” said Lew, assistant professor in the Preston M. Green Department of Electrical & Systems Engineering. It’s not simply a way to get a sharper picture. “This is a whole new way of validating the trustworthiness of each detail within a scientific image.

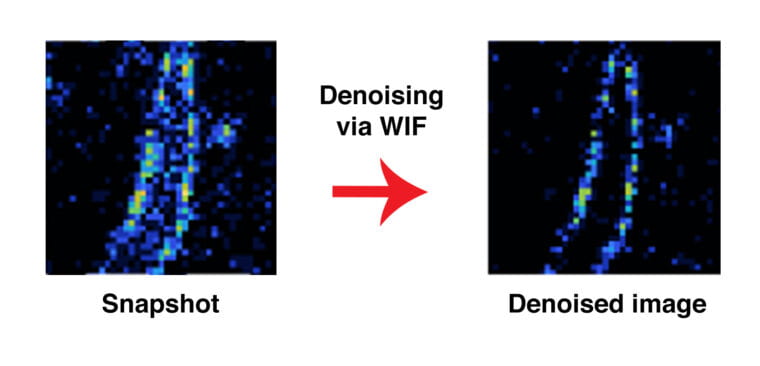

“It’s not about providing better resolution,” he added of the computational method, called Wasserstein-induced flux (WIF). “It’s saying, ‘This part of the image might be wrong or misplaced.’”