Blood draws are no fun.

They hurt. Veins can burst, or even roll — like they’re trying to avoid the needle, too.

Oftentimes, doctors use blood samples to check for biomarkers of disease: antibodies that signal a viral or bacterial infection, such as SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, or cytokines indicative of inflammation seen in conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and sepsis.

These biomarkers aren’t just in blood, though. They can also be found in the dense liquid medium that surrounds our cells, but in a low abundance that makes it difficult to be detected.

Until now.

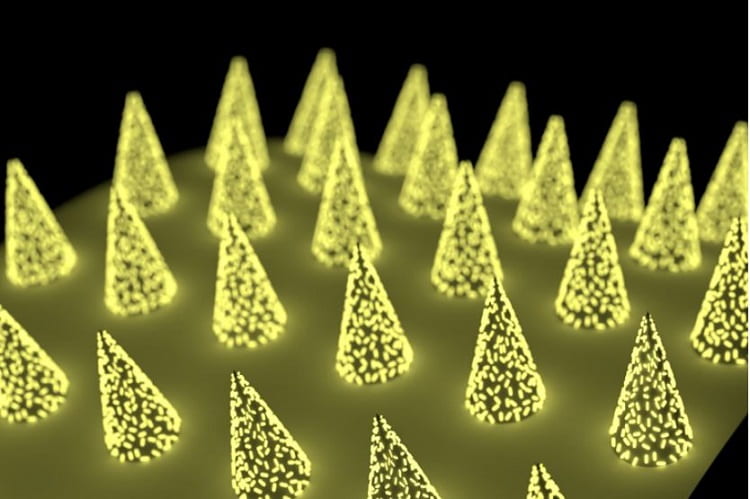

Engineers at the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis have developed a microneedle patch that can be applied to the skin, capture a biomarker of interest and, thanks to its unprecedented sensitivity, allow clinicians to detect its presence.

The technology is low cost, easy for clinicians or patients themselves to use, and could eliminate the need for a trip to the hospital just for a blood draw.

The research, from the lab of Srikanth Singamaneni, the Lilyan & E. Lisle Hughes Professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering & Material Sciences, was published online Jan. 22 in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

In addition to the low cost and ease of use, these microneedle patches have another advantage over blood draws, perhaps the most important feature for some: “They are nearly pain-free,” Singamaneni said.

Finding a biomarker using these microneedle patches is similar to blood testing. But instead of using a solution to find and quantify the biomarker in blood, the microneedles directly capture it from the liquid that surrounds our cells in skin, which is called dermal interstitial fluid (ISF). Once the biomarkers have been captured, they’re detected in the same way — using fluorescence to indicate their presence and quantity.

ISF is a rich source of biomolecules, densely packed with everything from neurotransmitters to cellular waste. However, to analyze biomarkers in ISF, conventional method generally requires extraction of ISF from skin. This method is difficult and usually the amount of ISF that can be obtained is not sufficient for analysis. That has been a major hurdle for developing microneedle-based biosensing technology.