Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis is joining the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) new research network focused on the study of senescent cells, a rare and important population of cells that is difficult to study but vital for understanding aging and the diseases of aging, including cancer and neurodegeneration. The goal is to help researchers develop new therapies that target cellular senescence to prevent or treat such diseases and improve human health.

Washington University will receive $7.5 million over five years to support the research.

The Cellular Senescence Network (SenNet) is supported by the NIH Common Fund and overseen by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The NIH will provide a total of about $125 million to 16 research centers over five years, pending available funds. The NIH has plans to expand SenNet through additional awards in the future.

The NIH is establishing SenNet to identify and describe senescent cells across multiple tissues throughout the body, in various states of health and disease, and at many ages across the human life span. Harnessing tissue samples from model organisms and people, the national network will provide freely accessible atlases of senescent cells, including information about the differences among them and the molecules they produce.

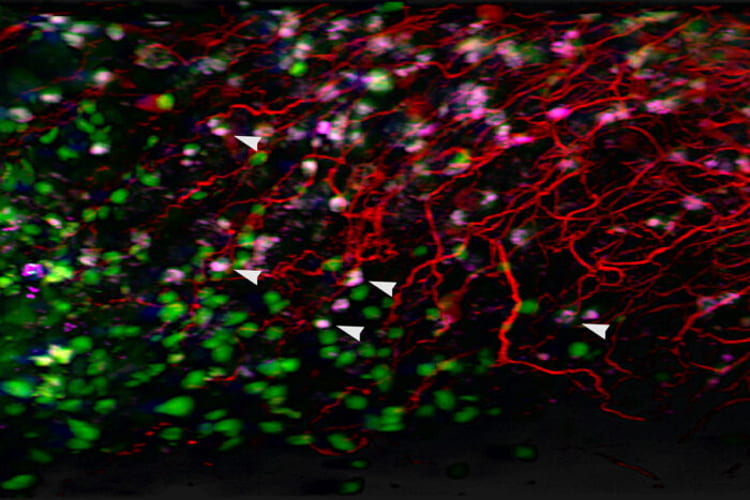

Washington University School of Medicine will serve as one of eight tissue-mapping centers. With a focus on bone marrow and liver, Washington University researchers will map the location and function of senescent cells in many samples of these specific tissues. Such research could shed light on the development of cancers of the blood and liver as well as metabolic disorders such as fatty liver disease.

The Washington University Senescence Tissue Mapping Center (WU-SN-TMC) will be led by principal investigator Li Ding, PhD, a professor of medicine and of genetics; and co-principal investigators Feng Chen, PhD, an associate professor of medicine; Ryan C. Fields, MD, the Kim and Tim Eberlein Distinguished Professor of Surgery; and Sheila A. Stewart, PhD, the Gerty Cori Professor of Cell Biology & Physiology and a professor of medicine.

“We are excited and proud to be a part of this national effort to understand cellular senescence,” Ding said. “These cells are quite mysterious. We don’t have good ways of detecting senescent cells in the body. They have lost their ability to divide, and some think that they are more fragile than normal cells. They also secrete a characteristic set of proteins as part of the ‘senescence associated secretory phenotype.’ Senescent cells are not cancerous, but they can lead to inflammation that sets the stage for cancer to develop along with other diseases that we associate with aging. Our group will map out senescent cells in bone marrow and liver samples in an effort to understand their spatial distribution and molecular signature in different tissue environments and at different ages.”