Pain from an injured back, shoulder or hip can make a person feel frustrated, anxious or even depressed. Many in health care may assume that when such injuries heal, mental health also improves. But a new study led by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis indicates that over the long term, symptoms of depression and anxiety often don’t subside when an orthopedic patient’s physical pain improves.

The researchers studied de-identified data from the medical charts of more than 11,000 patients treated in Washington University orthopedic clinics over a period of almost seven years. They found that symptoms of anxiety improved only when a patient had major improvements in physical function — but that even significant improvements in physical function were not associated with meaningful improvements in depression.

The study is published June 28 in the journal JAMA Network Open.

“We wanted to find out if patients have fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression as physical function improves and pain lessens,” said senior author Abby L. Cheng, MD, an assistant professor of orthopedic surgery. “The answer is that they mostly do not.”

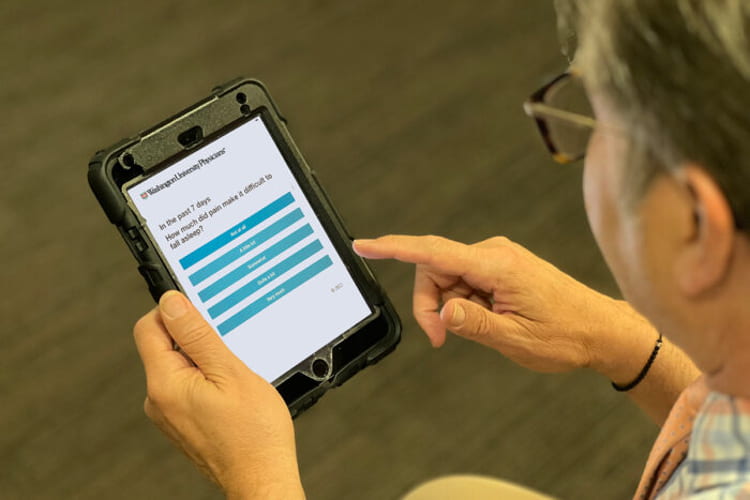

Each orthopedic patient treated at Washington University clinics is given a tablet upon check-in with a number of questions about whether their orthopedic problems are interfering with their lives. The list includes questions such as: “In the past seven days, how much did pain interfere with your ability to do household chores?” and, “In the past seven days, how much did pain make it difficult to fall asleep?” The questionnaire also asks about each person’s mental health and wellness.

“Our goal is to treat a person, not just fix a hip or a knee, and physical problems are connected to mood and anxiety, even to depression,” Cheng said. “Patients have a lot going on, and it’s difficult to provide good care without taking the big picture into account.”