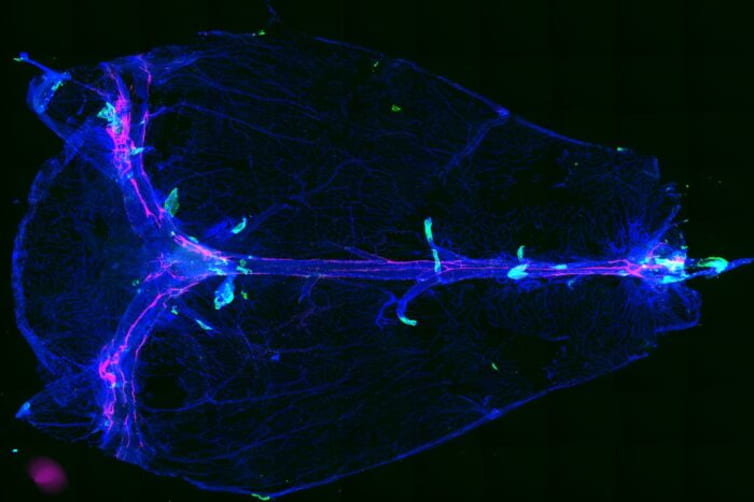

Scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found passageways that connect the brain to vessels that carry fluid waste out of and away from the brain. The newly discovered anatomical structures, found in mice and people, are like tiny gates, allowing waste to leave the brain and enter lymphatic vessels, where immune cells monitor it for signs of danger or infection.

These structures can be likened to airport security checkpoints. Molecules and fluid move in both directions through the gates, but immune cells are tightly regulated. Under normal conditions, immune cells are not allowed past security — similar to sharp objects, firearms and other potential weapons in an airport.

“Any opening can become a weak point when safeguards fail,” explained Jonathan Kipnis, PhD, the Alan A. and Edith L. Wolff Distinguished Professor of Pathology & Immunology and a BJC Investigator. “We have identified a previously unknown route that immune cells can use to access the brain in diseases driven by inflammation. We think these structures, and the cells and molecules strategically positioned around the gates to control passage, can help lead to new drugs for neuroinflammatory diseases.”

The findings are available Feb. 7 in Nature.

Immune cells and molecules play an important role in normal brain development and function, and in neurological conditions with an inflammatory component, such as Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease.

“The immune system communicates with the brain using molecules that cross from the dura mater to the brain,” said Kipnis, who in 2015 discovered the presence of lymph vessels in the dura mater, the outer tissue layer enveloping the brain underneath the skull. “But miscommunication between the brain and the immune system can have detrimental effects on brain function, including memory and behavior.”