The immune system is the brain’s best frenemy. It protects the brain from infection and helps injured tissues heal, but it also causes autoimmune diseases and creates inflammation that drives neurodegeneration.

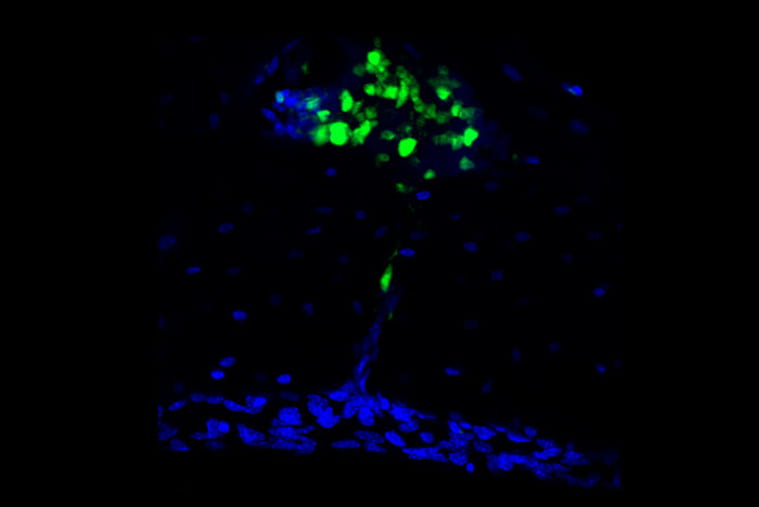

Two new studies in mice suggest that the double-edged nature of the relationship between the immune system and the brain may come down to the origins of the immune cells that patrol the meninges, the tissues that surround the brain and spinal cord. In complementary studies published June 3 in the journal Science, two teams of researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis unexpectedly found that many of the immune cells in the meninges come from bone marrow in the skull and migrate to the brain through special channels without passing through the blood.

These skull-derived immune cells are peacekeepers, dedicated to maintaining a healthy status quo. It’s the other immune cells, the ones that arrive from the bloodstream, that seem to be the troublemakers. They carry genetic signatures that mark them as likely to promote autoimmunity and inflammation, and they become more abundant with aging or under conditions of disease or injury. Taken together, the findings reveal a key aspect of the connection between the brain and the immune system that could inform our understanding of a wide range of brain disorders.

“There has been this gap in our knowledge that applies to almost every neurological disease: neuro-COVID, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, brain injury, you name it,” said Jonathan Kipnis, PhD, the Alan A. and Edith L. Wolff Distinguished Professor of Pathology & Immunology and a BJC Investigator. Kipnis is the senior author on one of the papers. “We knew immune cells were involved in neurological conditions, but where were they coming from? What we’ve found is that there’s a new source that hasn’t been described before for these cells.”

Earlier this year, Kipnis showed that immune cells stationed in the meninges keep tabs on the brain. As part of these new studies, Kipnis and Marco Colonna, MD, the Robert Rock Belliveau, MD, Professor of Pathology and the senior author on the other paper, independently launched projects to find where such cells come from. Kipnis focused on the innate arm of the immune system and Colonna on the adaptive arm. Innate immune cells are responsible for inflammation, which helps defend against infection and heal injuries, but also can damage tissues and contribute to degenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Adaptive immune cells are capable of specifically targeting undesirables such as viruses and tumors, but they also can mistakenly home in on the body’s own healthy tissues, resulting in autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis.